Glacial Erosion

Glacial erosion is a powerful geomorphic agent, capable of dramatically altering landscapes. The mechanics of glacial erosion and how glaciers flow are important to understand in order to link these processes to changes in the larger environment.

Learning Goals

- Identify the basic phenomena involved in determining glacial flow and articulate how glacial flow is modulated by the environment.

- Sketch a basic block diagram for a flowing glacier and identify the stresses, including basal shear stress, and associated contributors on the ice body.

- Define glacial erosional mechanisms and underline the importance of the ice-bed interface in determining glacial behavior.

Overview

Glaciers. You’ve definitely heard of them and, at this time of year in Minnesota, can probably imagine what it would be like to actually visit one. But, what are they and how do they work to shape landscapes and landscape processes? In this “week” of our course I’ll be taking you through the basics of glacial processes and how these processes, in turn, shape landscapes.

Here’s a picture I took in March 2020 of our team (including Andy) walking across the Perito Moreno glacier in Patagonia, Argentina.

We’ll begin by learning a bit about glacial erosion and glacial sliding so that we can understand what goes on directly within and around the ice to shape landscapes.

Then, we’ll move to an overview of glacial landforms, to see the direct implications of glacial erosion and sliding on the landscape as the glacier moves through it (from small, centimeter-scale glacial striations to miles-long moraine complexes).

Finally, we’ll learn about paraglacial landscape evolution, or the non-glacial processes that are directly triggered by glaciation. These processes can extend far beyond the ice margin and persist long after the glacial ice has melted. In fact, Minnesota is still currently experiencing many processes that could be described as paraglacial that were triggered by the Laurentide Ice Sheet, which covered much of Canada and parts of Minnesota at the Last Glacial Maximum (around 20,000 years ago).

There’s a lot more to glaciers and glacial geology than we can possibly cover in this short week. But, my hope is that you’ll come away from this week with a new appreciation of the massive geomorphic power of glaciation and how landscapes– past, present, and future– are shaped by glacial processes.

My Research in the Southern Patagonian Ice Field

Throughout the next few “lectures”, I’ll be using images and data from the fieldwork I was able to complete with Andy and several others from our research group from February to March 2020 in Southern Patagonia, Argentina. Most of my photos are of the Perito Moreno glacier, Fitz Roy, the Santa Cruz River, and Upsala Glacier. All of these features are closely related to (or a part of) the Southern Patagonian Ice Field.

A Google Satellite view of the tip of South America and the location of our fieldwork in Southern Argentina. Note the Southern Patagonian Ice Field, just west of the dropped pin.

The focus of this research is to understand the ice dynamics and environmental response to glaciation since the Little Ice Age. The Little Ice Age was a period of cooling that took place from the 1400s-1700s. These cool temperatures were nowhere near the level of the formal Ice Age (hence, the use of the world “Little”), but temperatures were unusually low during this period, compared to the present. In fact, temperatures got so cold during this time that the River Thames in London would regularly freeze over, allowing for regular “Frost Fairs” directly on the river ice. Paintings of these fairs are quite common.

Thames Frost Fair, 1683-84 by Thomas Wyke, courtesy of Wikipedia.

Following this (geologically brief) period of colder temperatures, global temperatures have since seen a considerable increase in temperature, augmented greatly by post-Industrial Revolution carbon emissions.

Since then the ice has retreated. This retreat is part of ongoing ice retreat since the Last Glacial Maximum. However, ice weighs a lot and, as a result, the crust rebounds when the ice retreats. This is called glacial isostatic adjustment, or the movement of crust in relation to the motion of glacial ice. The overall focus of this research is to understand the changes in the ice and surrounding environment of the Southern Patagonian Ice Field since the Little Ice Age.

The photos I show here will mostly be related to more general glacial topics. However, I will take some time to explain a bit about my research in the context of these topics, in hopes of giving you more real-world context of how glacial processes look like in-person.

Glacier Mass Balance

Glaciers are, generally, quite large (though that is becoming increasingly not the case, due to climate warming). As someone that has been fortunate to work on a glacier, I can confirm this simple fact.

The Perito Moreno glacier is approximately 19 miles long and covers roughly 97 square miles with ice. Here’s a picture of me as scale to show just how large this glacier really is.

Because glaciers are large and because they’re on the Earth’s surface, gravity acts upon them and causes them to flow. However, you may have noticed that glaciers do not simply slip downhill, leaving no ice behind as they do so. Instead, as glaciers flow, ice closer to the end of the glacier (what we call the terminus) melts while, near the top (head) of the glacier ongoing snowfall allows for the generation of new glacial ice.

This process, known as glacier mass balance is (as the name would imply) a balance between melting (ablation) and growing (accumulation) ice and allows for the glacier to flow continuously.

This short, very high quality video gives an overview of glacier mass balance, including accumulation, ablation, and the altitude on the ice where these two processes are equal (what we call the the Equilibrium Line Altitude (ELA)).

3D Rendering- Amalia Glacier

Overview of glacial features and glacier flow on a 3D rendering of the Amalia Glacier on the Reclus Volcano in Chile. 3D rendering courtesy of Camilo Rada.

Glacier Block Diagram and Basal Shear Stress

Mini-lecture using a block diagram to derive the equation for basal shear stress for a sliding glacier.

Glacial Erosional Mechanisms

Ice motion performs erosional work on the glacial bed and, as a result, generates glacial erosion. Glacial erosion is mostly encompassed by two main processes: glacial abrasion and glacial quarrying.

Glacial abrasion, or when small rock fragments are dragged along a glacier bed by sliding ice, generally makes the bed smoother. Think of this process as similar to sandpaper moving across a continuous wood surface. Over time, (with continuous abrasion) the “wood” is smoothed out and polished.

Glacial quarrying, in comparison, is when rock chunks (greater than 1 cm) are picked up from the bed as the glacier flows, leaving behind small indents from where the fragments were taken. As a result, glacial quarrying generally makes the bed rougher and is a key generator of bed roughness. This is similar to sandpaper moving across wood surface with many knots and chunks that can get picked up.

A knot in a wood plank. If this piece of wood were sanded, this knot would likely get picked up, leaving behind a large hole and, overall, increasing the roughness of this piece of wood. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

With both of these processes bed roughness can alter glacier sliding speed and glacial stability. Thus, the ice-bed interface plays an important role in determining the overall behavior of the glacier.

Another, additionally important mechanism for glacial erosion is the process of dissolution, where ice flowing over a carbonate bed is able to dissolve the rock directly using subglacial water. This can have huge implications in the right geologic setting but, because it is limited to certain lithologies, it’s not a main topic of our discussion here

Importance of the Glacial Bed

The ice-bed interface is also important in determining how a glacier will behave because its physical characteristics can dramatically alter ice flow.

Cold vs Warm Bed

A cold ice-bed interface does not allow the ice to flow as well, as ice can freeze directly to the bed, causing the ice to be held in place there. This inhibits glacial flow and, as a result, glacial erosion.

A warm ice-bed interface can allow for subglacial water to build up between the ice and the bed, acting essentially as a lubricant to allow the ice to flow more easily and rapidly. Too much water at the bed will allow the glacier to flow so quickly that erosion is diminished. However, with the right balance of subglacial water, a glacier is able to flow at a pace that maximizes glacial erosion. Subglacial water also plays a major role in a glacier’s hydrology (something we won’t get into in too much detail here, but a very interesting topic!).

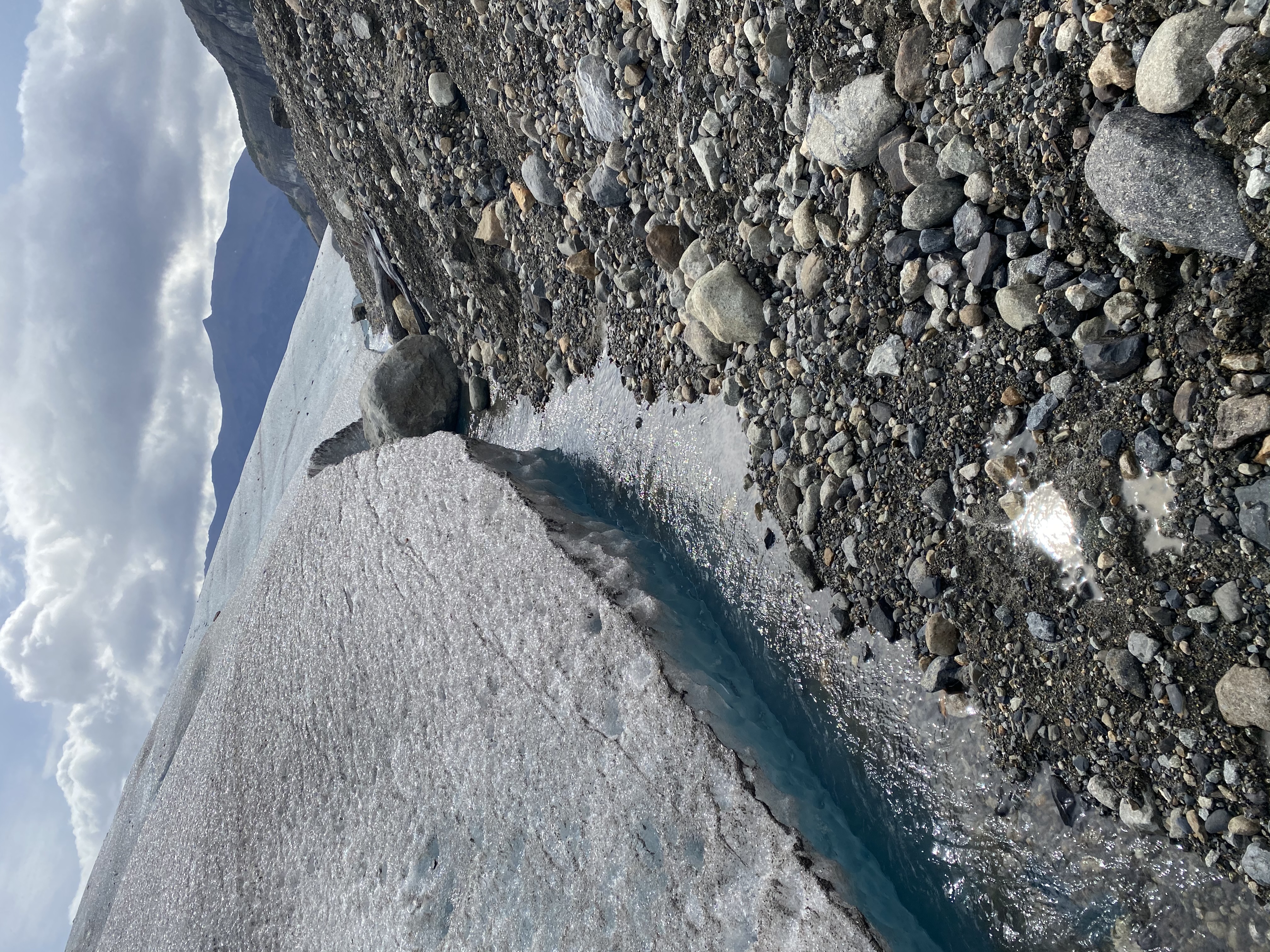

A picture of the side of the Perito Moreno glacier. Water flowing along and underneath the ice allows for faster glacial sliding rates.

Tying It All Together

So far we’ve talked about glacial sliding, basal shear stress, and the mechanisms of glacial erosion. Now we’ll move to our next section where we’ll talk about the result of this glacial erosion and glacial deposition on the landscape in the generation of glacial landforms.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.