Introduction to the Fluvial System

The fluvial system comrpises all parts of the landscape impacted by water flow across the surface. In includes headwaters streams, river channels, valleys, terraces, and floodplains.

Learning Goals

- Know the definition and components of the fluvial system.

- Be introduced to several concepts to be discussed later on and know where those concepts fit in the broader picture of geomorphology.

The Fluvial System

The fluvial system begins when surface water converges on hillslopes, forming small channels. These channels eventually form larger and larger streams and rivers that carve the landscape and move sediment. In this introductory podcast, I introduce these alongside several key concepts, including:

- The hillslope-to-fluvial (or hillslope–channel) transition

- Bedrock and alluvial rivers

- Detachment- and transport-limited rivers

- The geneneral geographic setting of rivers from source (uplands or mountains) to sink (enclosed basins or the ocean)

- Geogrpahical terminology surrounding river systems

Videos

These videos by Darron Gedge, secondary school geography teacher in New Zealand. They have excellent visuals and only require a few small caveats (possibly simplifications that he made to explain the processes to school students) in order to explain them.

Erosion and sedimentation: How rivers shape the landscape

This first video provides a good description of fluvial processes from the sources of the rivers to the sea, with one exception. The author states that flow slows down as a river moves downstream. In fact, river velocities remain remarkably constant through their whole course: even though they are steeper at the headwaters, they are deeper farther downstream. Recall Manning’s Equation or the Law of the Wall to see why this is. The real reason for the lower erosion farther downstream is because the river becomes transport-limited with high sediment inputs, and therefore cannot access the bedrock at the bottom of the channel.

Fluvial Processes - How Rivers Form

This video is also a good source of information and a better source of video content than I can make, but I need to add a few caveats.

Erosion:

- “Hydraulic action” – eroding the banks due to differential pressure between air and water – is not recognized to occur

- An important geomorphic process called “plucking” or “quarrying” – direct removal of bedrock blocks – is not included here

- Dissolution may be important, but often is not

Transportation:

- Replace “velocity” with “shear stress”. This is what transports sediment.

Deposition

- “Energy” is used in a vague way, and again, basically means “shear stress”. (This applies generally to other components of the video as well.)

- “Alluvium” applies to all sediment transported by flowing water, and not just to sediment in the river channel.

River profiles

- Turbulence is a mixing process, and does not slow the water down. (Friction, on the other hand, does.)

What types of Landforms are made by Rivers?

Notes:

- “River cliff” = “bluff” in the USA

- Again, velocity \(\rightarrow\) shear stress

- Again, “energy” \(\rightarrow\) shear stress

As an aside, the three types of deltas noted are built by different dominant processes:

- Arcuate/Fan and Cuspate: waves

- Bird’s Foot: fluvial

- Other deltas may be built in a way that is dominated by tidal sediment tranpsort; an example is the Ganga–Brahmaputra

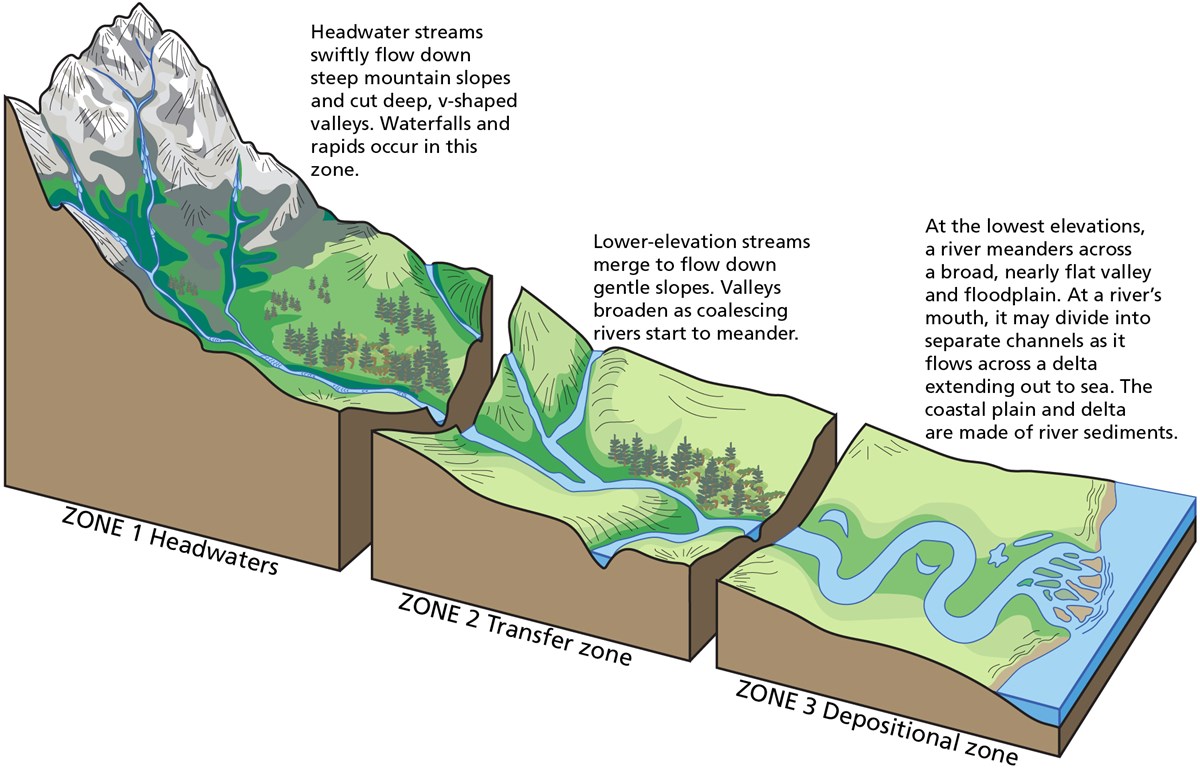

Diagram: The fluvial system, from source to sink

The fluvial system, by Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich of Colorado State University

The fluvial system, by Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich of Colorado State University

This diagram is from the USGS page on River Systems and Fluvial Landforms. This page provides additional entry-level information on fluvial geomorphology.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.