Weathering

Physical, chemical, and biological weathering processes break down material on Earth’s surface, forming regolith and soils.

Learning Goals

- Know the two (or three) types of weathering

- Know what regolith is

- Understand the concept of the “weathering engine”

Acknowledgment

Text lightly modified from Prof. Phil Larson’s Physical Geography course.

Why do geomorphologists care about weathering?

We study erosion and the landforms that result. Without weathering, we can’t have erosion!

- Step 1 = Decay in place (Chemical Weathering)

- Step 2 = Detachment, break off (Physical Weathering)

- Step 3 = Erode, move (Geomorphic/Earth Surface Processes)

- Step 4 = Deposit (Sedimentation)

Steps 1 and 2 are interchangeable, and biological processes can be involved in both: Step 1 is typically microbial, and Step 2 is typically associated with larger animals and plants.

Weathering: core information

Definition

Chemical, Physical, and Biological alteration of primary minerals that make up the “Parent Material” (rock or sediment that is being weathered).

Effect

Creates secondary minerals and dissolved ions

Two (three) types of weathering

- Physical Weathering – mechanical breakdown of rocks into smaller pieces (disaggregation)

- Chemical Weathering – breaking of chemical bonds (ionic, covalent) in minerals

- Biological Weathering – biologic agents that can physically or chemically weather minerals/rock, can enhance mechanical breakdown or catalyze reactions by changing environmental properties

Note: “biological” weathering is often not discussed, and subsumed into chemical weathering (microbially mediated reactions) and physical weathering (burrowing animals, bioturbation, tree roots, biofilm development adding cohesion, …)

Feedback

Physical and Chemical Weathering enhance each other

- Physical Weathering increases surface area susceptible to Chemical Weathering

- Chemical Weathering degrades the structural integrity of the rock, weakening it for Physical Weathering processes

Regolith

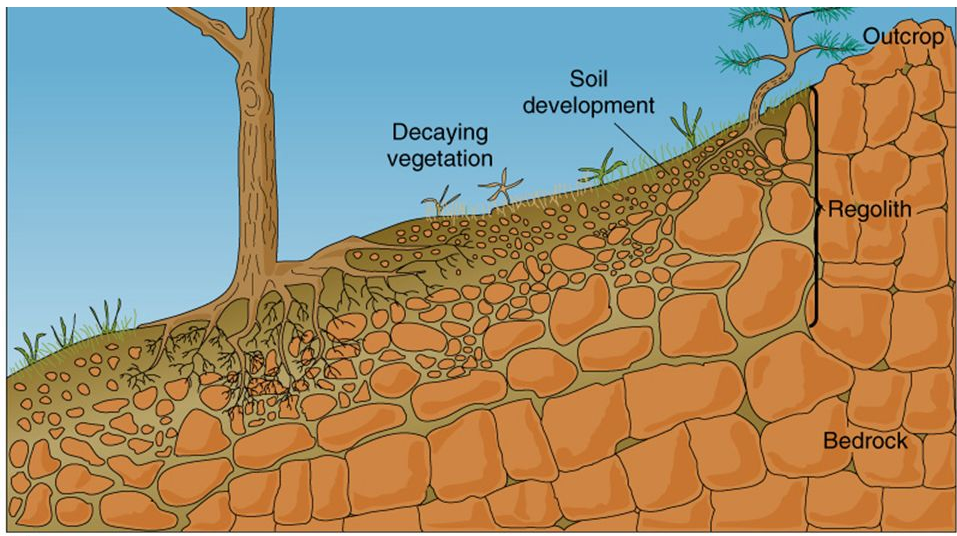

Weathering of bedrock creates “Regolith” – the layer of weathered material above unweathered bedrock. Regolith is formed in situ. The contact between regolith and unweathered bedrock is termed the “weathering front.”

- Regolith production allows for the production of soil and subsequent soil development (pedogenesis is the specialized term for soil development: pedo: soil, genesis: creation)

- When regolith production outpaces erosion, we call the landscape “weathering-limited”

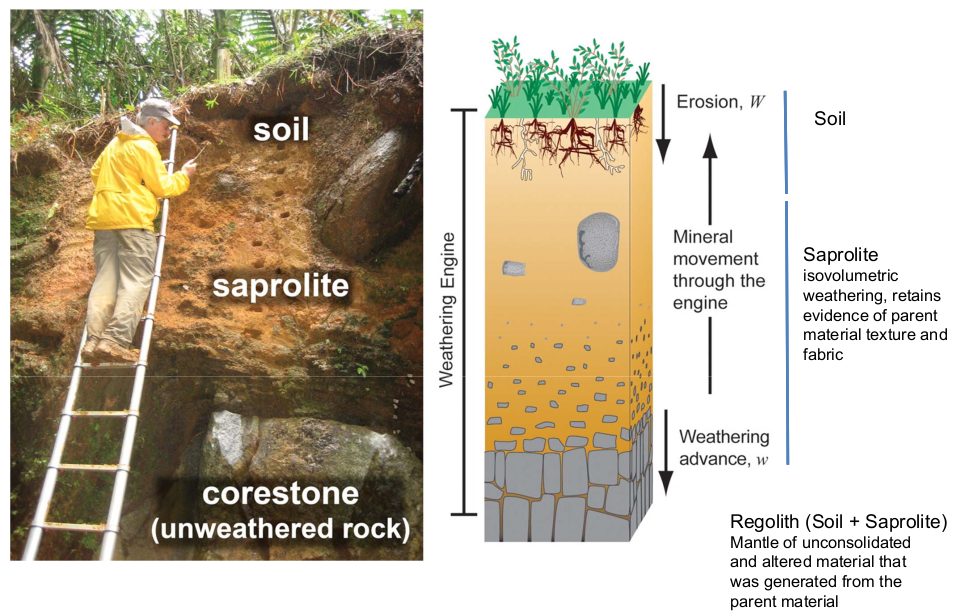

- When landscapes are weathering-limited, they can have thick accumulations of highly weathered regolith (saprolite) and highly developed soils.

- Saprolite = chemically altered (weathered), but in-place rock. Remains isovolumetric, but loses strength – often due to removal of more easily-weathered minerals (and therefore their replacement with void – pore – space that may be filled with air or water). Therefore strength and cohesion of saprolite are greatly reduced when compared to the parent rock.

Weathering breaks down rock. In a climate with vegetation, decaying organic matter mixes with weathered mineral material to form soil. (Reproduced via educational fair use; was not able to find original source.)

Weathering breaks down rock. In a climate with vegetation, decaying organic matter mixes with weathered mineral material to form soil. (Reproduced via educational fair use; was not able to find original source.)

Soils and the weathering engine

In landscapes underlain by bedrock, we use the term “weathering engine” to refer to the set of processes that occur in the soil column that act to weather bedrock. You can think of the soil column as a reactor hosting chemical, biological, and physical processes.

This weathering engine moves downwards into the rock as it weathers and removes material from the bottom.

Left: here you can see everything from the A (and possible O) horizon on top down to the R (parent material) horizon in the corestone at the bottom. Right: diagram of the weathering engine and weathering-front advance in an erosional portion of the landscape. (Figure from Brantley, 2007, Elements, as included by Markus Egli in his course notes on soil formation and weathering.)

Left: here you can see everything from the A (and possible O) horizon on top down to the R (parent material) horizon in the corestone at the bottom. Right: diagram of the weathering engine and weathering-front advance in an erosional portion of the landscape. (Figure from Brantley, 2007, Elements, as included by Markus Egli in his course notes on soil formation and weathering.)

Depositoinal regions (“cumulative” soils)

In landscapes with net deposition of unconsolidated material, this zone above bedrock becomes thicker over time, sometimes to the point that soils are completely buried and preserved as “paleosols”. Benath very thick blankets of unconsolidated material (e.g., river sediments, glacial till, wind-blown silt or sand), weathering of the bedrock surface may slow or even stop due to its great distance from the surface and the associated physical and chemical gradients and biological activity.

Erosional regions (“erosional soils”)

On landforms experiencing net erosion, such as steep hillslopes (remember the R for relief term in the soil-forming factors!), material is consistently stripped from the top of the soil column. At the same time, weathering produces new regolith at the bedrock interface. In this way, the whole soil profile is translating downwards through time as combined geomorphic and soil-forming processes modify Earth’s surface.

Video

For a set of good visuals of weathering processes and a voiceover to take you through it, I recommend Mike Sammartano’s Weathering, Erosion, and Deposition - Part 1. These professionals can put together a much nicer video than I can, and there is a lot of great material on soils and weathering out there!

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.