Form and Process

The landforms of Earth’s surface and the processes that form them connect and feed back into one another.

Learning Goals

- Appreciate that processes operating in the Earth system sculpt the landscape.

- Also appreciate that the landforms themselves can shape their environments and the geomorphic process domains that exist there, impacting the dominant processes that occur.

- Learn about the feedbacks between form and process that lead to distinctive landform patterns on Earth’s surface. These “patterns in nature” are everywhere, and often provide important clues into the evolution of Earth’s surface and how the processes that shape it function.

Video lecture

Form, process, and another point of view on introducing geomorphology

This short introductory video by Peter Knight of Keele University gives some quick examples of how landforms and the processes that shape them are connected.

Examples of linked form and process, with feedbacks

Orographic precipitation

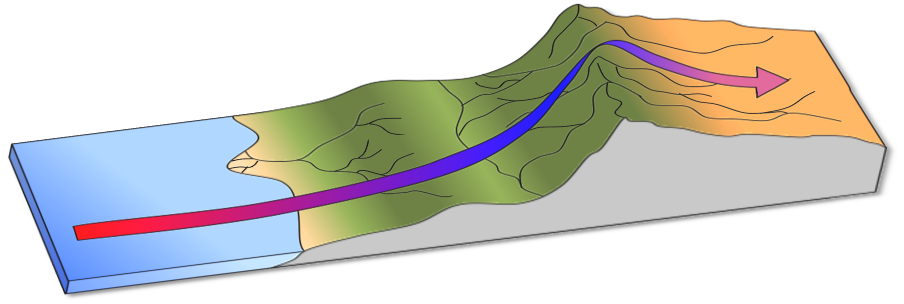

Orographic precipitation on a mountain range. Surface processes tend to make the wetter side have a longer and gentler slope, unlike what is pictured here.

Orographic precipitation on a mountain range. Surface processes tend to make the wetter side have a longer and gentler slope, unlike what is pictured here.

- Tectonic forces uplift mountain belts

- These steep lands begin to erode via hillslope and fluvial processes

- Eventually, the mountains become high enough that passing clouds rise, condensing their water and dropping vast amounts of rain on the windward side

- This rain makes erosion more efficient, potentially altering the shape of the mountain range and causing its drainage divide to migrate towards the more slowly eroding drier side.

Google Maps view of the San Francisco Bay Area stretching across the Sierra Nevada mountain range into the U.S. state of Nevada. Note the transition from wet west to dry east.

Google Maps view of the San Francisco Bay Area stretching across the Sierra Nevada mountain range into the U.S. state of Nevada. Note the transition from wet west to dry east.

Fluvial erosion

- Water starts to erode a small channel

- This channel then becomes a low point on the landscape, such that other portions of the land surface start to drain towards it

- This additional water the further erodes the valley and enlarges the drainage

- This process continues, with larger drainage basins capturing and consuming smaller drainage basins until the common form of hills and valleys that cover fluvially dominated landscapes emerges

This simple example from Taylor Perron’s landscape-evolution modeling group at MIT shows “first-order” drainages (those with just one channel) eroding into a landscape and “self-organizing” – that is, creating a pattern without any external forcing – as the land uplifts.

This larger scale model, also from the MIT group, demonstrates how rivers compete to reshape the landscape, building basins and the ridges that divide them. In this class, you will learn how to work with similar models.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.