Viscosity (and Elasticity)

Internal resistance to flow.

Learning Goals

- Know that viscosity is the measure of resistance to flow

- Have mental examples for high and low-viscosity materials

- Know how the spring constant relates to elasticity, and this in turn by analogy to viscosity

Elasticity and Viscosity

Viscosity is a measure of resistance to flow. In the abstract, it is a fluid-mechanics analogy to Young’s Modulus in Hooke’s Law for elastic materials. You may recall the spring constant from an introductory physics course, which relates to Young’s modulus and is helpful to recall when learning about viscosity.

Hooke’s law and Young’s Modulus

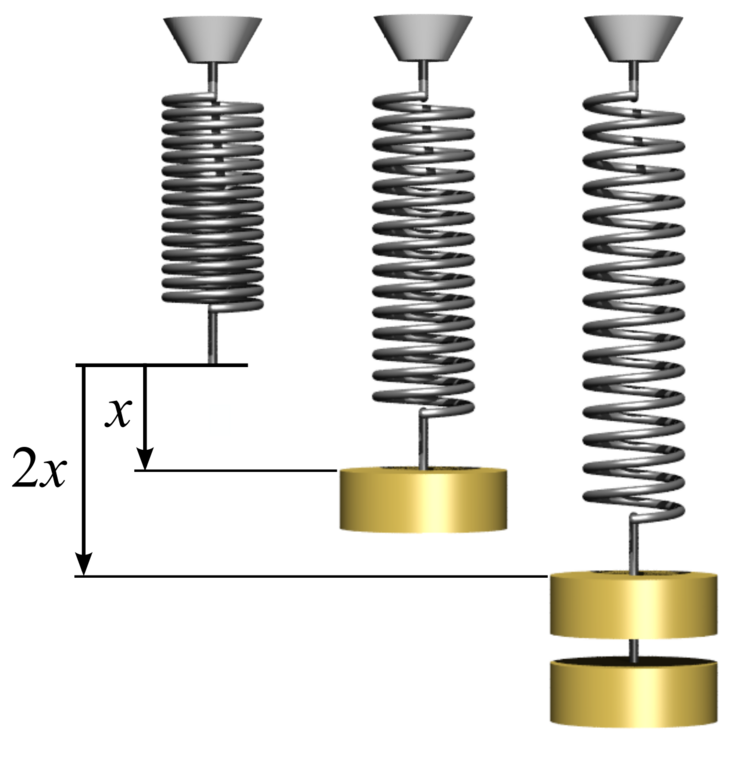

Linear relationship between stress and strain with a spring: image from Wikimedia Commons.

Linear relationship between stress and strain with a spring: image from Wikimedia Commons.

First-semester physics courses typically introduce the linear relationship between an applied force and the lengthening or shortening of a spring.

\[F = k x\]Here, \(F\) is a force, \(k\) is the spring constnt, and \(x\) is some amount of displacement.

The spring constant wraps (heh!) together many different variables.

- How long is the spring? Longer springs have more coils that can deform, and therefore become more easily stretched or compressed.

- How thick is the wire? Thicker wires are stiffer.

- What is the material? Different materials have different rigidities.

One of the reasons that we study springs in physics – arguably, the main reason – is because they are such a good analogy to elastic materials in general. But in order to understand the material properties, we want to strip away these questions of length and wire width. So therefore, we do two things:

- We normalize deformations to the length, $l$, of the spring. This removes the effect of the spring length.

- We normalize by the cross-sectional area of the material. This removes the effect of the wire thickness.

To address (1), we reframe $x$ as a change in length of the material $\Delta l$ divided by its starting length, $l$. To address (2), we normalize the force by the cross-sectional area of the spring material, $A$. This gives us:

\[\frac{F}{A} = E \frac{\Delta l}{l}\]What is this $E$ term? This is Young’s Modulus. It is like a spring constant, except it depends only only the properties of the material – not on its geometry.

Now, let’s apply a couple of definitions. A force per unit area is defined as a stress, $\sigma$:

\[\sigma = \frac{F}{A}\]A change in distance per distance is a unitless quantity called a strain, $\varepsilon$:

\[\varepsilon = \frac{\Delta l}{l}\]At this point, it is straightforward to rewrite the above equation with Young’s modulus to one that links stress and strain.

\[\sigma = E \varepsilon\]Viscosity and strain rate

The above example is of a linear elastic material because there is a direct proportionality between stress and strain. If you graphed their relationship, it would be a straight line with a slope given by Young’s Modulus, $E$. We often just call this an “elastic material”, with the “linear” part implied.

Similarly, a linear viscous fluid (or simply, a “viscous fluid”) has a linear relationship between stress, \(\sigma\), and strain rate, \(\dot{\varepsilon} = \mathrm{d}\varepsilon / \mathrm{d}t\). This is the defining difference between an elastic and a viscous material: an elastic material deforms to an extent that is determined by the stress, and will return to its original shape when the stress is removed. A viscous fluid, on the other hand, deforms at a rate given by the applied stress. And when this stress is removed, the fluid stops deforming, but doe snot return to its original shape.

In equation form:

\(\sigma = \mu \frac{\mathrm{d}\varepsilon}{\mathrm{d}t} = \mu \dot{\varepsilon}\),

where \(\mu\) is the viscosity, which we also call the dynamic viscosity. (Note/aside: those of you in geophysics courses may see \(\eta\) as viscosity and $\mu$ as one of the elastic Lamé parameters. Tough noogies. Conflicting conventions were established long ago, and wish as we might, we can’t do much to change that until someone improbably creates a scientific board to create a set of standards and – perhaps more improbably – the scientists actually listen to them.)

In geomorphology, this is primarily important because:

- Water is a linear viscous fluid

- This general concept of viscosity will be helpful to bear in mind as you work through understanding flows in general.

Videos

Viscosity comparison

Examples of flow down an inclined plane of different household fluids to illustrate different viscosities. There’s no need to watch past 3:14; this link will start you at 2:18, which will save you some set-up… and the jingle!

If you feel like watching another video

For enjoyment and outrage at the abuse of laboratory glassware:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.