Problem Set: Rating curves, flood management, and geomorphically effective discharge

Develop a theoretical “rating curve” – stage–discharge relationship – for a rectangular river channel with a floodplain. Consider how you would efficiently measure flow velocity in the field by incorporating insights from the Law of the Wall. Think about how human modifications of the landscape might affect flow and shear stress distributions. Consider the impacts of artificial levees on rivers.

Learning Goals

Overarching goal: Understand the concept of a geomorphically effective flood, and in the process learn about stream gauging.

- Find the depth at which to measure mean flow in a channel during a stream survey.

- Construct and understand stage–discharge rating curves.

- Apply the Law of the Wall and Manning’s Equation to create a theoretical stage–discharge relationship for a channel and floodplain.

- Convert your stage–discharge curve to a curve of shear stresses and combine this with a flow-duration curve to find the geomorphically effective flood.

- Consider how building levees might impact channel dynamics.

- Learn how levees affect communities along rivers.

The setup

You have been tasked with understanding the flow and channel dynamics in a reach of river. The surrounding communities are considering installing levees, but they want to know first what impact they will have on the channel dynamics. They also want to know how high the levees should be to enclose a 100-year flood. They do not have data on river stage and discharge, so they want you to calculate it.

Channel characteristics

Approximately rectangular. Units given in square brackets at the end of each bullet point; all equations are desgined for SI units.

- 50 m wide (\(b\)) [m]

- 2 m deep (this is the bankfull flow depth, referred to in the notes as \(h_{bf}\)) [m]

- Slope of 0.0005 (\(S\)) [–]

- Sandy bed with bedforms; the combination of flow resistance against these and the individual sand grains gives a bed-roughness length $z_0 = 1$ mm (Law of the Wall) [mm]

- Median sand grain size \(D_{50}\) = 0.5 mm. You may use this in place of the generic grain size, \(D\), wherever it is requested. [mm]

Floodplain characteristics

- Perfectly planar

- Slope of 0.0007 (slightly steeper than the channel because of the lack of sinuosity). This is also “\(S\)”, but here is used only with the Manning Equation for flow velocity over the floodplain. The channel slope, above, should be used for sediment-transport calculations. [–]

- 1 km wide valley floor, \(B\). (Note: this includes the width of the channel; subtract the channel width to find the width of the floodplain alone) [km]

- Mostly covered in light brush and trees; this is a place with strong flow seasonality, with little to no flow during winter, so overbank events will happen during summer. Recall the Manning’s n table

Important equations to recall

Law of the Wall

\[u(z) = \frac{u_\tau}{\kappa} \ln\left(\frac{z}{z_0}\right)\]Manning’s Equation

\[\bar{u} = \frac{1}{n} h^{2/3} S^{1/2}\]Here, \(\bar{u}\) refers to the vertically averaged velocity. In Question 1, you will solve for \(\bar{u}\) by manipulating the Law of the Wall, above. These two expressions are based on different ways of calculating \(\bar{u}\). They needn’t look identical, and indeed will not!

Depth–slope product

In all questions except for 6, we will assume that there is steady, uniform flow. Because of this:

\[\bar{\tau_b} = \rho g h S\]Also recall that:

\[u_\tau = \sqrt{ \frac{\tau_b}{\rho} }\]Enegelund–Hansen sand-transport formula (new!)

This formula relates dimensionless basal shear stress, \(\tau_b^*\), to dimensionless discharge of sand per unit width of channel, \(q_s^*\), as:

\[q_s^* = \frac{0.05}{C_f} ( \tau_b^* )^{5/2}\]Here, \(^*\) indicates a term that is nondimensionalized. This means that we have multiplied or divided the dimensional terms for sediment discharge per unit width (\(q_s\)) and basal shear stress (\(\tau_b\)) to create new terms in which all the units cancel out.

Why would we cancel out the units? Well, if we didn’t, we would need to balance units of stress to the 5/2 power with those of sediment discharge. By nondimensionalizing, we are able to create any arbitrary mathematical relationship between these variables, and know that this will remain dimensionally consistent.

In this case:

\[q_s^* = \frac{q_s}{\left(\frac{\rho_s - \rho}{\rho}\right)^{1/2} g^{1/2} D^{3/2}},\]where \(q_s\) is sediment discharge per unit channel width [m2/s], and

\[\tau_b^* = \frac{\tau_b}{\left(\rho_s - \rho\right) g D}.\]Here, \(\rho_s = 2650\) kg m-3 is sediment (i.e., quartz) density, \(\rho = 1000\) kg m-3 is water density, and \(D\) is sediment grain size, for which you can use the \(D_{50}\) value.

\(C_f\) is the Darcy–Weisbach friction factor. It varies with flow depth, but for the sake of not getting too bogged down in equations and being able to focus on the core concepts here, I have calculated \(C_f = 0.05\) to be a reasonable (and very convenient!) estimate.

\(\tau_b^*\) provides a good demonstration of why we nondimensionalize. Conceptually, extra shear stress pushes on the grains and increases the possibility that they be entrained in the flow. On the other hand, grains that are heavier – which scales with their submerged density (\(\rho_s - \rho\)), diameter (\(D\)), and the gravitational acceleration (\(g\)) – are more stable. Thus one can also view \(\tau_b^*\) as:

\[\tau_b^* = \frac{\text{Strength of flow pushing grains to move}}{\text{Grain stability}}.\]As you can see, nondimensionalization is our way of lumping opposing drivers in the same term in order to create intuitive variables that may be combined easily with one another.

You’ll just have to trust me for now that this conceptual argument works in terms of the formal physics as well. Alternatively, you can read the derivation of the force balance on a grain written by Wiberg and Smith, 1987).

1. Mean flow velocity (20 points)

In order to calculate flow velocity in the channel with the provided information, you need to use the Law of the Wall. However, the formulation above provides the velocity as a function of elevation.

Part A

Using the Law of the Wall and the mean-value theorem (MVT), solve for the mean (i.e., vertically averaged) flow velocity \(\bar{u}\) [m/s]. Note that this is the vertically averaged \(\bar{u}\) that is used, e.g., for Manning’s Equation. It is not the time-averaged \(\bar{u}\) that is used for the Reynolds, i.e., turbulent, decomposition. Your goal is to find the vertically averaged velocity in order to connect flow depth [m] and discharge [m3/s]. When applying the MVT, recall that flow velocity is assumed to go to 0 at a small elevation \(z = z_0\) [m] (due to the fact that we do not take into account the laminar sublayer). Consider a flow of arbitrary depth \(h\) [m], and express the solution with respect to this depth.

As a reminder of your calculus days, the MVT provides the average value of a function, \(f(x)\), over a a range of the independent variable (\(x\)) extending from \(x_0\) to \(x_1\):

\[\overline{f(x)} = \frac{1}{x_1-x_0} \int_{x_0}^{x_1}{f(x) \mathrm{d}x}\]Here’s a hint that will help you to create a simpler solution and solve Part B. After you finish your initial solution, think about the flow depth with respect to the roughness from grains and bedforms. In most natural streams, \(h \gg z_0\). Therefore, look for places (hint: likely two) where you can remove a number that will be small because of this.

Part B

You are quite clever, and after solving for mean velocity, realize that at some depth within the channel, the water flow velocity will be exactly equal to its mean. Because you are often working on contracts with limited time, knowing that you or your staff could measure flow velocity at only one flow depth would save you effort in the field. Based on knowing the mean velocity and your work from above, solve for the elevation within the flow at which the local flow velocity will equal the mean flow velocity as a function of the flow depth, \(h\).

2. Stage–discharge relationship (30 points)

Part A

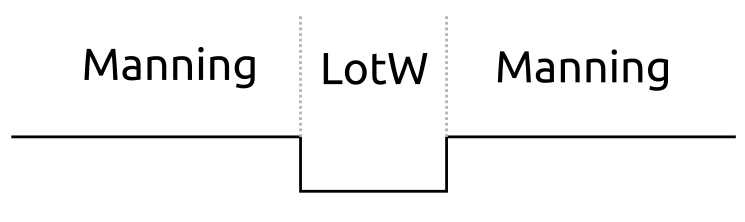

Using the above information on the river and floodplain and your now-obtained equation for mean flow velocity, calculate the relationship between river stage and discharge for stages of up to 4 meters above the river bed. Note that we have provided the information to use the Law of the Wall for flows in (and above) the channel, wherein your work in 1A, above may help. For the floodplain, we provide information necessary to use Manning’s Equation. Therefore, you will have to combine both approaches as shown in the figure below:

Show your work, including equations (as applicable) and provide a plot with stage on the y axis and discharge on the x axis. A spreadsheet (or writing a bit of computer code) may be a good way to do this, but is certainly not the only way!

On your plot, mark the location of the bankfull discharge. Note the numerical value of this discharge.

Part B

Describe in a few sentences why you think this plot has the shape that it does? What does this tell you about how stage and discharge vary? Do you note anything special at the bankfull stage (and discharge)?

Part C

Finally, many of the following questions are going to require you to convert discharge into stage. You might, however, notice that you have used multiple equations to compute the stage–discharge relationship and that stage appears in multiple terms – including within a logarithm! Empirical stage–discharge rating curves, on the other hand, often use a simple power–law fit of the type \(h = \lambda_1 Q^{\lambda_2}\), where $\lambda_1$ and $\lambda_2$ are the coefficient and exponent of an empirical fit, respectively. This equation is simpler, and may be easily inverted (i.e., you can easily rearrange it to solve for \(h\) or \(Q\)). Using a spreadsheet or programming language, fit this generic power-law equation to your computed stage–discharge relationship (likely represented as a set of points where you have calculated it at different levels), and plot this fit. Provide the best-fitting parameters as well. You can use this equation to help you answer the questions below.

Hint: Don’t worry if the curve fit doesn’t look very nice. The key point here is to go through the process and get practice with the relationships between these key measureables and variables.

3. Flood risk and the flood-frequency curve (20 points)

Based on regional meteorological data, comparisons with nearby streams, and a kindhearted desire to keep the functional form of equations simple, you estimate that the discharge down your river should scale with return period – the average number of years between two floods of a given magnitude – as:

\[Q = 170 \log_{10}(5 P_R),\]where \(P_R\) indicates the return period of that flood in years.

Important note: This equation is not dimensionally consistent! This means that no theory should be able to explain it; it is just an arbitrarty observed relationship between two variables. Therefore, \(Q\) is volumetric water discharge [m3/s] whereas \(P_R\) is return period [1/yr]. There’s a lot of empiricism in observational hydrology. Maybe one of you will help to find the deeper meaning and answer behind this!

Part A

First, calculate the return period of the bankfull flow.

Part B

Second, plot the flood stage against return period for the 1–500 year floods (or, to make it easier for you for Question 4, the 0.3–200-year floods – we’ll accept either) based on the rating curve that you constructed in Question (2). This now gives you a mechanism to address questions related to flooding hazards and levee heights.

4. Geomorphically effective discharge for natural flow (40 points)

If you want some background on this analysis, you can see the original paper by Wolman and Miller (1960). They use stress, whereas we use discharge to connect the geomorphic change to the hydrology.

Before building the levees, you want to see how they might impact flow and sediment in the channel and beyond the current reach of river. You start by considering the current natural flows in the channel and how they have shaped the channel.

As is typical, the levees that you are considering will lie immediately adjacent to the channel. So long as they are not overtopped, no water will flow onto the floodplain.

Part A

Knowing the depth–slope product, you can compute basal shear stress as a function of flow depth, \(\tau_b(h)\). Based on your stage–discharge curve, you can translate this into a basal shear stress as a function of river discharge, \(\tau_b(Q)\).

Using this, plot the bed-load (i.e., sand) sediment discharge (y axis) vs. water discharge (x axis) for the 0.3–200-year floods. Be sure to consider sediment discharge across the whole channel:

\[Q_s = q_s b.\]Consider the floodplain to be covered in thick enough vegetation that no significant erosion or sediment transport will be possible. This is in part a simplifying assumption, but is usually not a terrible one for moderate-sized floods.

Part B

Next, on another set of axes, plot the relative proportion of time that the river is at a certain flood stage (y axis) vs. water discharge (x axis). To represent the relative proportion of time that the river is at a certain flood stage in a simple way, we can just use the reciprocal of the flow return period (\(1/P\)). I write relative because this is not normalized to anything meaningful, but can help us to compare the frequency of one flow to another in this time series.

Part C

Now, multiply these together (i.e., \(Q_s/P\)) to obtain the amount of net sediment transport performed by events of different recurrence intervals. This will show you the relative geomorphic effectiveness of each flood: you should see that larger ones have a higher sediment-transport capacity but occur much more rarely. Plot this (sediment discharge times ) on the y axis and water discharge on the x axis.

Part D

Using this last plot, pick the the most geomorphically effective discharge; it should appear as a peak in the plot of \(Q_s/P\) vs. \(Q\). How does this compare to the bankfull discharge?

Hint: this number may not, as expected, correspond to bankfull discharge. Indeed, you may need to extend the range of floods that you are considering to find where this optimum lies. You can think about how this could relate to human modifications to the river channel. Also think about about how close a bankfull discharge may be to that given here: is it in the ballpark or not?

5. Levee height (30 points)

Part A

The citizens living in the valley hired you to estimate the minimum height of a levee needed to protect against a 200-year flood. (They had discussed protecting against a 100-year flood, as is common. However, due to increasing heavy rains with climate change, they are not sure that the future storms will follow the historical statistics, and want to play it safe.) How tall should this levee be such that the 200-year flood stage will be exactly at its crest?

Note 1: Engineers would design with a bit of a factor of safety atop this; here we are not considering the “little extra to be sure”.

Note 2: Once the levees are installed, the channel will no longer be able to spill out onto its floodplain. Therefore, you will have to recalculate your stage–discharge relationship to consider the flows through the channel alone. You needn’t worry about those that are greater than 2 meters spilling out onto the floodplain; this is why you are building levees!

Show the new stage–discharge relationship and describe provide the minimum levee height to contain the 200-year flood. Again, a spreadsheet may help here.

Part B

Next, as a brief thought exercise, write 2–3 sentences about what you think this levee will do to shear stress and sediment transport within this reach of the river.

Part C

Finally, compare the sediment (i.e., sand) discharge from this reach of river for a 100-year flood with and without levees using the Engelund–Hansen formula, above. Note that the reaches of river downstream from where the levees will be installed will still experience natural flows. After making your calculation, venture a ~2-sentence guess about how this might change the river upstream and downstream of where the levees are, and about how where the sediment from the reach with levees might go.

6. Levee Wars (30 points)

Recently, communities in the US have been engaging in a dramatic slow-motion battle by building levees on their side of the river higher. These “Levee Wars” are exacerbated by different state laws and the amount of money different communities have, and may run afoul of regulations from the US Army Corps of Engineers. In 2018, the Saint Anthony Falls Laboratory collaborated with Lisa Song and Al Shaw of ProPublica to demonstrate how this happens.

First, gain a bit of background by watching the video, below:

Then, go to their investivative study. It starts with the same video (so you could watch it here instead), and then goes on to demonstrate the impacts of levees through some interactive activities and descriptions.

Part A

The study’s authors note the benefits of “setback” levees. Provide an argument for how these help. You may use your words and/or simple calculations, and/or make reference to those calculations that you made in answering prior questions. Experiment with the interactive activities on the ProPublica page, created through experiments at SAFL, as these might help you to think through the answer.

Part B

The study’s authors also show how water levels change for a given discharge after levees are built – that is, the rating curve changes. We will first focus on the zone right where the levees were built (their panel B). In answering Questions 2 and 5, you should have already constructed pre- and post-levee rating curves. Now, plot these side-by-side or atop each other, and in 1-2 sentences, describe the difference and why it occurs.

Part C

The ProPublica study’s authors note that flood risks become higher in the zone upstream of the levees. This is due to the backwater effect – the upstream water becomes backed up behind the higher water between the levees due to the pressure pressure force exerted on the upstream flow. Earlier in class, we defined a backwater length as the the distance over which a river significantly responds to this backwater effect.

In the normal case, when a river flows into the ocean, we calculate the backwater length, \(l_{bw}\), as:

\[l_{bw} = \frac{h}{S},\]where \(h\) and \(S\) are the channel depth and slope, respectively. In the case of the ocean, however, the whole body of water is standing and merges to meet the river’s surface. In the case that we are considering here, levee construction adds some additional depth of flow atop the standard natural flow depth of the river, and it is this additional flow depth that makes the flow become nonuniform. Therefore, we slightly redefine the backwater length as:

\[l_{bw} = \frac{\Delta h}{S},\]where \(\Delta h\) is the difference in stage between the pre- and post-flood levees.

Old text: this is more work. You can do this, but need not: Using the two rating curves that you plotted together in Part B, calculate and plot the distance upstream over which you expect water levels to increase as a result of the levees (i.e, the backwater length) on the \(y\) axis, and the river discharge on the \(x\) axis. Comment on this plot and its implications for river management; you may use the ProPublica material as a guide.

Updated, easier approach: For the 1-, 10-, 50-, and 100-year floods, calculate the length of the backwater that is created as a result of the emplacement of the levees. This is the distance upstream over which you expect water levels to increase as a result of the levees’ presence. Describe in words what this result means, as well as its implications for river and flood management; you may use the ProPublica material as a guide.

Hint: in answering this question, it may be useful to create a table with columns: Return Period, Discharge, Depth with levees, Depth without levees, Differential depth (optional), backwater length.

Hint 2: because of the difficulty of inverting the Law of the Wall, you can just estimate these water depths based on nearby values in your spreadsheet.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.